There is no shortage of reminders these days about how easily peace can turn into violence. Protests turn into disturbances very easily — all too often resulting in senseless crime directed against people who have no connection to the grievance that sparked the unrest.

The Crown Heights riots of 1991 were a different, and fortunately still singular, kind of event in America. They constituted the first time, perhaps since the lynching of Leo Frank in 1915 Georgia, that a rampant violent mob targeted Jews. Hopefully it will be the last.

Looking back, it’s hard to understand how the rumor that a Jewish ambulance squad refused to treat a dying black child spread so quickly, and for so long, without being effectively dispelled. In reality, it was the police who told the Hatzolah ambulance crew, who wanted to save the child’s life, to leave the scene for their own safety.

A “perfect storm” of tragedy mixed with dysfunction followed. There was a lack of sufficient official, accurate information channeled through community leaders when it was needed most. And to top that off, there was incredibly weak leadership at the police department and in City Hall.

Into this nest of chaos (as police, for whatever reason, failed to forcefully quell the riots with mass arrests) walked Yankel Rosenbaum. One man was later convicted of inciting the mob with “get the Jew;” and the mob did just that. And many others went free who were just as guilty.

The vacuum of competence seemed to follow Rosenbaum from the unprotected streets to Kings County Hospital, where an untreated stab wound led to his death.

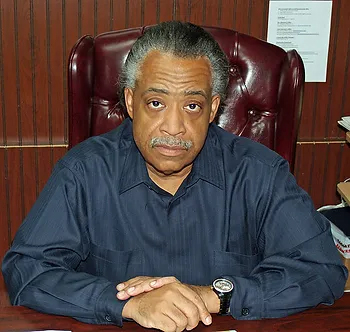

The next day, things would go from bad to worse. The Reverend Al Sharpton, then an angry preacher, didn’t change the narrative when he arrived in Crown Heights. He viewed this as another case of racism, almost as if the Hassidic driver had targeted the black child. The streets echoed with chants of “No justice, no peace,” even though there was already no peace, and there had been no chance to properly analyze the accident.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of these events in 2011, Rev. Sharpton admirably reflected on his actions and noted in a Daily News op-ed that he should have chosen his words at the time more carefully, especially at the funeral of the deceased child, Gavin Cato.

“With the wisdom of hindsight, let’s be clear,” he wrote. “Our language and tone sometimes exacerbated tensions and played to the extremists rather than raising the issue of the value of this young man whom we were so concerned about.” He added that he also should have expressed concern about the value of Yankel Rosenbaum’s life and that “there was no justification or excuse for violence.”

But this was not enough, according to Rosenbaum’s brother, Norman, who noted that the preacher has yet to demand justice for the 28 people who took part in the mob that attacked Yankel. Few if any people were ever charged with lesser counts of vandalizing property and terrorizing Crown Heights Jews in their homes.

Looking back on the events, so many people still try to present an alternative version of events: blacks and Jews scuffling with each other over neighborhood issues, as the New York Times tried to cast it, or the legitimate indignation of the rioters spilling over into unfortunate violence because of the August heat (and unemployment in the black community).

But the truth, as Norman Rosenbaum put it, was that the riots at their core were a result of people, mostly agitators from outside Crown Heights, exploiting a tragedy to vent their resentment of Jews in general and the Crown Heights Hassidim in particular — and to inflict harm on innocent people.

If we are to learn any lesson at all, it is how leaders such as Sharpton and Mayor David Dinkins failed to act quickly and unambiguously to stop the violence.

Investigators have never disproven what Mayor Dinkins has long maintained: That he never ordered the police to let the rioters vent. But that doesn’t matter. As his successor, Rudy Giuliani, showed, the city’s chief executive gets the credit when things are running well because he appoints the leaders, and they answer to him.

I believe that a similar incident would not happen in 2016. Today, we’re able to Tweet and email accurate information to catch up to falsehoods and quickly organize leaders to restore calm; furthermore, with police alertness perpetually high out of terrorism concerns, it’s likely a strong show of force would stop such an outbreak.

Finally, New Yorkers have learned to vote smarter. Hopefully when they look at the next election for City Hall, they’ll factor in the important question of, when there’s a perfect storm, who will be holding the umbrella?

Originally Published: The Algemeiner